October 29th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Definition

Traumatic brain injury occurs when an external mechanical force causes brain dysfunction.

Traumatic brain injury usually results from a violent blow or jolt to the head or body. An object penetrating the skull, such as a bullet or shattered piece of skull, also can cause traumatic brain injury.

Mild traumatic brain injury may cause temporary dysfunction of brain cells. More serious traumatic brain injury can result in bruising, torn tissues, bleeding and other physical damage to the brain that can result in long-term complications or death.

Symptoms

Traumatic brain injury can have wide-ranging physical and psychological effects. Some signs or symptoms may appear immediately after the traumatic event, while others may appear days or weeks later.

Mild traumatic brain injury

The signs and symptoms of mild traumatic brain injury may include:

Physical symptoms

- Loss of consciousness for a few seconds to a few minutes

- No loss of consciousness, but a state of being dazed, confused or disoriented

- Headache

- Nausea or vomiting

- Fatigue or drowsiness

- Difficulty sleeping

- Sleeping more than usual

- Dizziness or loss of balance

Sensory symptoms

- Sensory problems, such as blurred vision, ringing in the ears, a bad taste in the mouth or changes in the ability to smell

- Sensitivity to light or sound

Cognitive or mental symptoms

- Memory or concentration problems

- Mood changes or mood swings

- Feeling depressed or anxious

Moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries

Moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries can include any of the signs and symptoms of mild injury, as well as the following symptoms that may appear within the first hours to days after a head injury:

Physical symptoms

- Loss of consciousness from several minutes to hours

- Persistent headache or headache that worsens

- Repeated vomiting or nausea

- Convulsions or seizures

- Dilation of one or both pupils of the eyes

- Clear fluids draining from the nose or ears

- Inability to awaken from sleep

- Weakness or numbness in fingers and toes

- Loss of coordination

Cognitive or mental symptoms

- Profound confusion

- Agitation, combativeness or other unusual behavior

- Slurred speech

- Coma and other disorders of consciousness

When to see a doctor

Always see your doctor if you or your child has received a blow to the head or body that concerns you or causes behavioral changes. Seek emergency medical care if there are any signs or symptoms of traumatic brain injury following a recent blow or other traumatic injury to the head.

The terms “mild,” “moderate” and “severe” are used to describe the effect of the injury on brain function. A mild injury to the brain is still a serious injury that requires prompt attention and an accurate diagnosis.

Causes

Traumatic brain injury is caused by a blow or other traumatic injury to the head or body. The degree of damage can depend on several factors, including the nature of the event and the force of impact.

Injury may include one or more of the following factors:

- Damage to brain cells may be limited to the area directly below the point of impact on the skull.

- A severe blow or jolt can cause multiple points of damage because the brain may move back and forth in the skull.

- A severe rotational or spinning jolt can cause the tearing of cellular structures.

- A blast, as from an explosive device, can cause widespread damage.

- An object penetrating the skull can cause severe, irreparable damage to brain cells, blood vessels and protective tissues around the brain.

- Bleeding in or around the brain, swelling, and blood clots can disrupt the oxygen supply to the brain and cause wider damage.

Common events causing traumatic brain injury include the following:

- Falling out of bed, slipping in the bath, falling down steps, falling from ladders and related falls are the most common cause of traumatic brain injury overall, particularly in older adults and young children.

- Vehicle-related collisions. Collisions involving cars, motorcycles or bicycles — and pedestrians involved in such accidents — are a common cause of traumatic brain injury.

- About 20 percent of traumatic brain injuries are caused by violence, such as gunshot wounds, domestic violence or child abuse. Shaken baby syndrome is traumatic brain injury caused by the violent shaking of an infant that damages brain cells.

- Sports injuries. Traumatic brain injuries may be caused by injuries from a number of sports, including soccer, boxing, football, baseball, lacrosse, skateboarding, hockey, and other high-impact or extreme sports, particularly in youth.

Explosive blasts and other combat injuries. Explosive blasts are a common cause of traumatic brain injury in active-duty military personnel. Although the mechanism of damage isn’t yet well-understood, many researchers believe that the pressure wave passing through the brain significantly disrupts brain function.

Traumatic brain injury also results from penetrating wounds, severe blows to the head with shrapnel or debris, and falls or bodily collisions with objects following a blast.

The people most at risk of traumatic brain injury include:

- Children, especially newborns to 4-year-olds

- Young adults, especially those between ages 15 and 24

Adults age 75 and older

The above information is taken from the following sources:

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/basics/symptoms/con-20029302

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain injury/basics/symptoms/con-20029302

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/basics/causes/con-20029302

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/basics/risk-factors/con-20029302

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 28th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

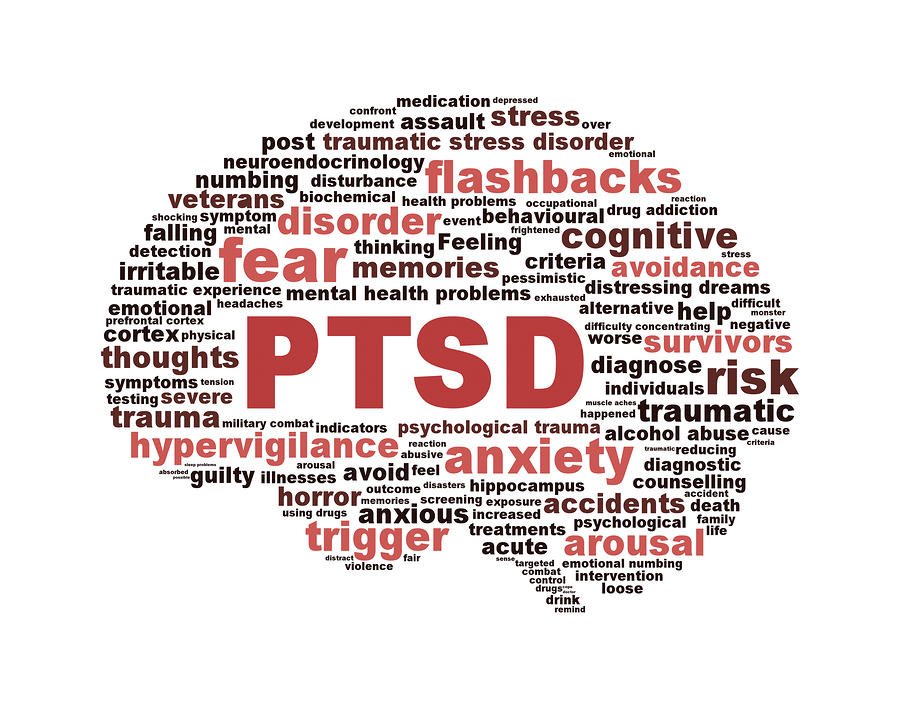

PTSD symbol with a brain outline isolated on white background. Anxiety disorder symbol conceptual design

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

What is Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

When in danger, it’s natural to feel afraid. This fear triggers many split-second changes in the body to prepare to defend against the danger or to avoid it. This “fight-or-flight” response is a healthy reaction meant to protect a person from harm. But in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this reaction is changed or damaged. People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened even when they’re no longer in danger.

PTSD develops after a terrifying ordeal that involved physical harm or the threat of physical harm. The person who develops PTSD may have been the one who was harmed, the harm may have happened to a loved one, or the person may have witnessed a harmful event that happened to loved ones or strangers.

PTSD was first brought to public attention in relation to war veterans, but it can result from a variety of traumatic incidents, such as mugging, rape, torture, being kidnapped or held captive, child abuse, car accidents, train wrecks, plane crashes, bombings, or natural disasters such as floods or earthquakes.

Signs & Symptoms

PTSD can cause many symptoms. These symptoms can be grouped into three categories:

- Re-experiencing symptoms

- Flashbacks—reliving the trauma over and over, including physical symptoms like a racing heart or sweating

- Bad dreams

- Frightening thoughts.

Re-experiencing symptoms may cause problems in a person’s everyday routine. They can start from the person’s own thoughts and feelings. Words, objects, or situations that are reminders of the event can also trigger re-experiencing.

- Avoidance symptoms

- Staying away from places, events, or objects that are reminders of the experience

- Feeling emotionally numb

- Feeling strong guilt, depression, or worry

- Losing interest in activities that were enjoyable in the past

- Having trouble remembering the dangerous event.

Things that remind a person of the traumatic event can trigger avoidance symptoms. These symptoms may cause a person to change his or her personal routine. For example, after a bad car accident, a person who usually drives may avoid driving or riding in a car.

- Hyperarousal symptoms

- Being easily startled

- Feeling tense or “on edge”

- Having difficulty sleeping, and/or having angry outbursts.

Hyperarousal symptoms are usually constant, instead of being triggered by things that remind one of the traumatic event. They can make the person feel stressed and angry. These symptoms may make it hard to do daily tasks, such as sleeping, eating, or concentrating.

It’s natural to have some of these symptoms after a dangerous event. Sometimes people have very serious symptoms that go away after a few weeks. This is called acute stress disorder, or ASD. When the symptoms last more than a few weeks and become an ongoing problem, they might be PTSD. Some people with PTSD don’t show any symptoms for weeks or months.

Do children react differently than adults?

Children and teens can have extreme reactions to trauma, but their symptoms may not be the same as adults. In very young children, these symptoms can include:

- Bedwetting, when they’d learned how to use the toilet before

- Forgetting how or being unable to talk

- Acting out the scary event during playtime

- Being unusually clingy with a parent or other adult.

Older children and teens usually show symptoms more like those seen in adults. They may also develop disruptive, disrespectful, or destructive behaviors. Older children and teens may feel guilty for not preventing injury or deaths. They may also have thoughts of revenge. For more information, see the NIMH booklets on helping children cope with violence and disasters. (from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) )

Who Is At Risk?

PTSD can occur at any age, including childhood. Women are more likely to develop PTSD than men, and there is some evidence that susceptibility to the disorder may run in families.

Anyone can get PTSD at any age. This includes war veterans and survivors of physical and sexual assault, abuse, accidents, disasters, and many other serious events.

Not everyone with PTSD has been through a dangerous event. Some people get PTSD after a friend or family member experiences danger or is harmed. The sudden, unexpected death of a loved one can also cause PTSD.

Why do some people get PTSD and other people do not?

It is important to remember that not everyone who lives through a dangerous event gets PTSD. In fact, most will not get the disorder.

Many factors play a part in whether a person will get PTSD. Some of these are risk factors that make a person more likely to get PTSD. Other factors, called resilience factors, can help reduce the risk of the disorder. Some of these risk and resilience factors are present before the trauma and others become important during and after a traumatic event.

Risk factors for PTSD include:

- Living through dangerous events and traumas

- Having a history of mental illness

- Getting hurt

- Seeing people hurt or killed

- Feeling horror, helplessness, or extreme fear

- Having little or no social support after the event

- Dealing with extra stress after the event, such as loss of a loved one, pain and injury, or loss of a job or home.

Resilience factors that may reduce the risk of PTSD include:

- Seeking out support from other people, such as friends and family

- Finding a support group after a traumatic event

- Feeling good about one’s own actions in the face of danger

- Having a coping strategy, or a way of getting through the bad event and learning from it

- Being able to act and respond effectively despite feeling fear.

Researchers are studying the importance of various risk and resilience factors. With more study, it may be possible someday to predict who is likely to get PTSD and prevent it.

Diagnosis

Not every traumatized person develops full-blown or even minor PTSD. Symptoms usually begin within 3 months of the incident but occasionally emerge years afterward. They must last more than a month to be considered PTSD. The course of the illness varies. Some people recover within 6 months, while others have symptoms that last much longer. In some people, the condition becomes chronic.

A doctor who has experience helping people with mental illnesses, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, can diagnose PTSD. The diagnosis is made after the doctor talks with the person who has symptoms of PTSD.

To be diagnosed with PTSD, a person must have all of the following for at least 1 month:

- At least one re-experiencing symptom

- At least three avoidance symptoms

- At least two hyperarousal symptoms

Symptoms that make it hard to go about daily life, go to school or work, be with friends, and take care of important tasks.

PTSD is often accompanied by depression, substance abuse, or one or more of the other anxiety disorders.

Treatments

The main treatments for people with PTSD are psychotherapy (“talk” therapy), medications, or both. Everyone is different, so a treatment that works for one person may not work for another. It is important for anyone with PTSD to be treated by a mental health care provider who is experienced with PTSD. Some people with PTSD need to try different treatments to find what works for their symptoms.

If someone with PTSD is going through an ongoing trauma, such as being in an abusive relationship, both of the problems need to be treated. Other ongoing problems can include panic disorder, depression, substance abuse, and feeling suicidal.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is “talk” therapy. It involves talking with a mental health professional to treat a mental illness. Psychotherapy can occur one-on-one or in a group. Talk therapy treatment for PTSD usually lasts 6 to 12 weeks, but can take more time. Research shows that support from family and friends can be an important part of therapy.

Many types of psychotherapy can help people with PTSD. Some types target the symptoms of PTSD directly. Other therapies focus on social, family, or job-related problems. The doctor or therapist may combine different therapies depending on each person’s needs.

One helpful therapy is called cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. There are several parts to CBT, including:

- Exposure therapy. This therapy helps people face and control their fear. It exposes them to the trauma they experienced in a safe way. It uses mental imagery, writing, or visits to the place where the event happened. The therapist uses these tools to help people with PTSD cope with their feelings.

- Cognitive restructuring. This therapy helps people make sense of the bad memories. Sometimes people remember the event differently than how it happened. They may feel guilt or shame about what is not their fault. The therapist helps people with PTSD look at what happened in a realistic way.

- Stress inoculation training. This therapy tries to reduce PTSD symptoms by teaching a person how to reduce anxiety. Like cognitive restructuring, this treatment helps people look at their memories in a healthy way.

Other types of treatment can also help people with PTSD. People with PTSD should talk about all treatment options with their therapist.

How Talk Therapies Help People Overcome PTSD

Talk therapies teach people helpful ways to react to frightening events that trigger their PTSD symptoms. Based on this general goal, different types of therapy may:

- Teach about trauma and its effects.

- Use relaxation and anger control skills.

- Provide tips for better sleep, diet, and exercise habits.

- Help people identify and deal with guilt, shame, and other feelings about the event.

- Focus on changing how people react to their PTSD symptoms. For example, therapy helps people visit places and people that are reminders of the trauma.

Medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two medications for treating adults with PTSD:

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

Both of these medications are antidepressants, which are also used to treat depression. They may help control PTSD symptoms such as sadness, worry, anger, and feeling numb inside. Taking these medications may make it easier to go through psychotherapy.

Sometimes people taking these medications have side effects. The effects can be annoying, but they usually go away. However, medications affect everyone differently. Any side effects or unusual reactions should be reported to a doctor immediately.

The most common side effects of antidepressants like sertraline and paroxetine are:

- Headache, which usually goes away within a few days.

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach), which usually goes away within a few days.

- Sleeplessness or drowsiness, which may occur during the first few weeks but then goes away.

- Agitation (feeling jittery).

- Sexual problems, which can affect both men and women, including reduced sex drive, and problems having and enjoying sex.

Sometimes the medication dose needs to be reduced or the time of day it is taken needs to be adjusted to help lessen these side effects.

The above information and more can be found here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 27th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

Question: What is Narcolepsy?

Answer: Narcolepsy is a neurological disorder that impacts 1 in approximately 2,000 people in the United States. Many people are unaware of the condition and go undiagnosed. The disease is a sleep disorder, involving irregular patterns in Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep and significant disruptions of the normal sleep/wake cycle. Narcolepsy can affect all areas of a person’s life including relationships with family and friends, education and employment, driving and public outings. While the cause of Narcolepsy is not completely understood, current research points to a combination of genetic and environmental factors that influence the immune system.

Question: What causes Narcolepsy?

Answer: Scientists have confirmed that Narcolepsy with cataplexy is caused by the loss of the two brain chemicals called hypocretins (orexins). These are neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of the sleep/wake cycle as well as other bodily functions (e.g., blood pressure and metabolism). The cause(s) of Narcolepsy without cataplexy are unknown. Further research is needed to determine why hypocretin cells are destroyed and to identify the exact trigger(s) of both forms of Narcolepsy.

Question: Is Narcolepsy inherited?

Answer: There appears to be some genetic predisposition to developing Narcolepsy with cataplexy, the most common form. About one quarter of the general population in the U.S. carries the HLA-DQB1* o602 genetic marker but only one person out of about 500 of these people will develop this form of Narcolepsy.

Question: Does Narcolepsy affect learning?

Answer: Although Narcolepsy does not affect intelligence, learning is sometimes affected by the symptoms. Study, concentration, memory, and attention span may be periodically impaired by sleep. Adjustments in study/work habits may be continually necessary. This can best be accomplished with the cooperation of school and employer personnel.

Question: How common is Narcolepsy?

Answer: It is estimated that there are over 200,000 persons with Narcolepsy in the United States, but only about 25%, or 50,000 of them, have been diagnosed. On average it takes over seven years from onset of symptoms until a diagnosis is established.

Question: Is Narcolepsy limited to certain groups of people?

Answer: Incidence of Narcolepsy can vary by ethnic group. The highest occurrence is found among the Japanese at one in about 600 and the lowest rate is among Israeli Jews at one in about 500,000. Narcolepsy affects both men and women equally.

Question: At what age do people get Narcolepsy?

Answer: Although any person can develop Narcolepsy at any age, the typical onset is in the second to third decade (between 10 – 30 years of age) of life.

Question: Can Narcolepsy be cured?

Answer: Currently no cure for Narcolepsy exists, nor any way to replace the missing Hypocretin. Treatment of Narcolepsy aims to relieve the symptoms. The symptoms of Narcolepsy can vary greatly from one person to another, as can the treatments and their effectiveness.

Question: What are the symptoms of Narcolepsy?

Answer: Narcolepsy has five primary symptoms:

- Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS) – An overwhelming sense of tiredness and fatigue throughout the day

- Cataplexy (C) – Events during which a person has no reflex or voluntary muscle control. For example knees buckle and even give way when experiencing a strong emotion – laughter, joy, surprise, anger or heads drop or jaws go slack from the same kind of stimuli

- Sleep paralysis – A limpness in the body associated with REM sleep resulting in temporary paralysis when the individual is falling asleep, or awakening. Episodes can last from a brief moment to several minutes.

- Hypnogogic hallucinations – Events of vivid audio and visual events that a person with narcolepsy experiences while falling asleep, or while awakening

- Disrupted Nighttime Sleep (DNS) – The inability to maintain sleep for more than a few hours at a time.

Other symptoms reported by people with Narcolepsy can include:

- Automatic Behavior (AB) – The performance of tasks that are often routine, dull or repetitive without conscious effort or memory.

- Memory Lapses – Difficulty in remembering recent events, actions or words

Question: How is Narcolepsy diagnosed?

Answer: Narcolepsy is diagnosed through a sleep study, a set of medical tests including an overnight Polysomnogram (PSG) and a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT). Even when cataplexy is clearly present, a sleep study is necessary to rule out sleep apnea and other possible sleep disorders contributing to EDS.

Narcolepsy often takes years to recognize in patients. Many medical conditions result in fatigue, thus physicians might not consider Narcolepsy. While new discoveries are being made about Narcolepsy and other sleep disorders, life with Narcolepsy remains challenging for many people with the condition. Narcolepsy Network hopes that the information, resources, and support provided here on our site and elsewhere through conferences and events will provide people with Narcolepsy both hope and a voice.

Question: How is Narcolepsy treated?

Answer: There are three approaches to treatment:

- Modern medications

- Lifestyle adjustments

- Complimentary or alternative therapy

By combining these approaches and balancing between treatments for Sleepiness and REM Intrusion, optimal control of symptoms can be reached. It is best to be under the care of a physician who is specially trained, Certified in Sleep Medicine, Board Certified in Neurology and experienced in treating Narcolepsy.

The following information and more can be found here and here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 26th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

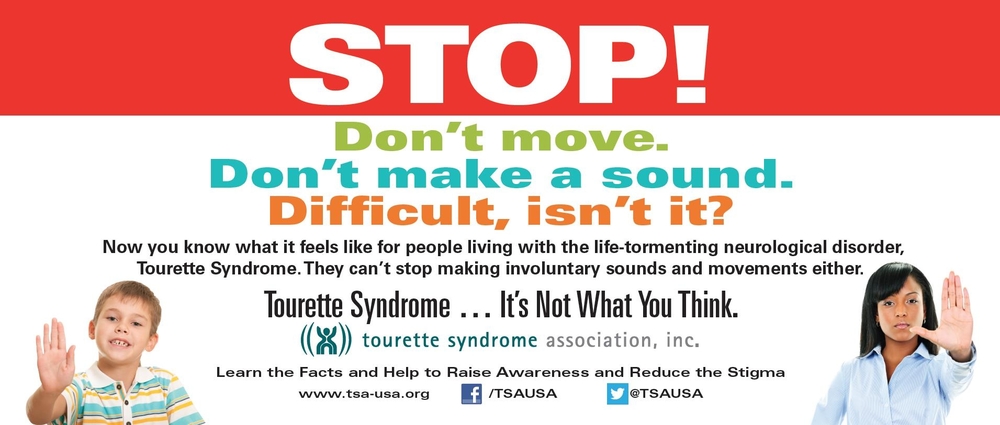

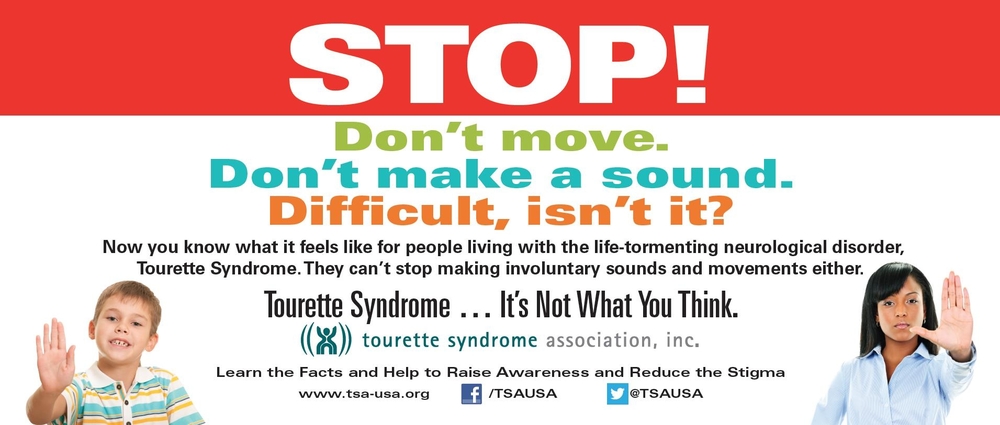

What is Tourette syndrome?

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neurological disorder characterized by repetitive, stereotyped, involuntary movements and vocalizations called tics. The disorder is named for Dr. Georges Gilles de la Tourette, the pioneering French neurologist who in 1885 first described the condition in an 86-year-old French noblewoman.

The early symptoms of TS are typically noticed first in childhood, with the average onset between the ages of 3 and 9 years. TS occurs in people from all ethnic groups; males are affected about three to four times more often than females. It is estimated that 200,000 Americans have the most severe form of TS, and as many as one in 100 exhibit milder and less complex symptoms, such as chronic motor or vocal tics. Although TS can be a chronic condition with symptoms lasting a lifetime, most people with the condition experience their worst tic symptoms in their early teens, with improvement occurring in the late teens and continuing into adulthood.

What are the symptoms?

Tics are classified as either simple or complex. Simple motor tics are sudden, brief, repetitive movements that involve a limited number of muscle groups. Some of the more common simple tics include eye blinking and other eye movements, facial grimacing, shoulder shrugging, and head or shoulder jerking. Simple vocalizations might include repetitive throat-clearing, sniffing, or grunting sounds. Complex tics are distinct, coordinated patterns of movements involving several muscle groups. Complex motor tics might include facial grimacing combined with a head twist and a shoulder shrug. Other complex motor tics may actually appear purposeful, including sniffing or touching objects, hopping, jumping, bending, or twisting. Simple vocal tics may include throat-clearing, sniffing/snorting, grunting, or barking. More complex vocal tics include words or phrases. Perhaps the most dramatic and disabling tics include motor movements that result in self-harm such as punching oneself in the face or vocal tics including coprolalia (uttering socially inappropriate words such as swearing) or echolalia (repeating the words or phrases of others). However, coprolalia is only present in a small number (10 to 15 percent) of individuals with TS. Some tics are preceded by an urge or sensation in the affected muscle group, commonly called a premonitory urge. Some with TS will describe a need to complete a tic in a certain way or a certain number of times in order to relieve the urge or decrease the sensation.

Tics are often worse with excitement or anxiety and better during calm, focused activities. Certain physical experiences can trigger or worsen tics, for example tight collars may trigger neck tics, or hearing another person sniff or throat-clear may trigger similar sounds. Tics do not go away during sleep but are often significantly diminished.

What is the course of TS?

Tics come and go over time, varying in type, frequency, location, and severity. The first symptoms usually occur in the head and neck area and may progress to include muscles of the trunk and extremities. Motor tics generally precede the development of vocal tics and simple tics often precede complex tics. Most patients experience peak tic severity before the mid-teen years with improvement for the majority of patients in the late teen years and early adulthood. Approximately 10-15 percent of those affected have a progressive or disabling course that lasts into adulthood.

Can people with TS control their tics?

Although the symptoms of TS are involuntary, some people can sometimes suppress, camouflage, or otherwise manage their tics in an effort to minimize their impact on functioning. However, people with TS often report a substantial buildup in tension when suppressing their tics to the point where they feel that the tic must be expressed (against their will). Tics in response to an environmental trigger can appear to be voluntary or purposeful but are not.

What causes TS?

Although the cause of TS is unknown, current research points to abnormalities in certain brain regions (including the basal ganglia, frontal lobes, and cortex), the circuits that interconnect these regions, and the neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine) responsible for communication among nerve cells. Given the often complex presentation of TS, the cause of the disorder is likely to be equally complex.

What disorders are associated with TS?

Many individuals with TS experience additional neurobehavioral problems that often cause more impairment than the tics themselves. These include inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder—ADHD); problems with reading, writing, and arithmetic; and obsessive-compulsive symptoms such as intrusive thoughts/worries and repetitive behaviors. For example, worries about dirt and germs may be associated with repetitive hand-washing, and concerns about bad things happening may be associated with ritualistic behaviors such as counting, repeating, or ordering and arranging. People with TS have also reported problems with depression or anxiety disorders, as well as other difficulties with living, that may or may not be directly related to TS. In addition, although most individuals with TS experience a significant decline in motor and vocal tics in late adolescence and early adulthood, the associated neurobehavioral conditions may persist. Given the range of potential complications, people with TS are best served by receiving medical care that provides a comprehensive treatment plan.

How is TS diagnosed?

TS is a diagnosis that doctors make after verifying that the patient has had both motor and vocal tics for at least 1 year. The existence of other neurological or psychiatric conditions can also help doctors arrive at a diagnosis. Common tics are not often misdiagnosed by knowledgeable clinicians. However, atypical symptoms or atypical presentations (for example, onset of symptoms in adulthood) may require specific specialty expertise for diagnosis. There are no blood, laboratory, or imaging tests needed for diagnosis. In rare cases, neuroimaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT), electroencephalogram (EEG) studies, or certain blood tests may be used to rule out other conditions that might be confused with TS when the history or clinical examination is atypical.

It is not uncommon for patients to obtain a formal diagnosis of TS only after symptoms have been present for some time. The reasons for this are many. For families and physicians unfamiliar with TS, mild and even moderate tic symptoms may be considered inconsequential, part of a developmental phase, or the result of another condition. For example, parents may think that eye blinking is related to vision problems or that sniffing is related to seasonal allergies. Many patients are self-diagnosed after they, their parents, other relatives, or friends read or hear about TS from others.

How is TS treated?

Because tic symptoms often do not cause impairment, the majority of people with TS require no medication for tic suppression. However, effective medications are available for those whose symptoms interfere with functioning. Neuroleptics (drugs that may be used to treat psychotic and non-psychotic disorders) are the most consistently useful medications for tic suppression; a number are available but some are more effective than others (for example, haloperidol and pimozide).

Unfortunately, there is no one medication that is helpful to all people with TS, nor does any medication completely eliminate symptoms. In addition, all medications have side effects. Many neuroleptic side effects can be managed by initiating treatment slowly and reducing the dose when side effects occur.

Behavioral treatments such as awareness training and competing response training can also be used to reduce tics. A recent control trial called Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Tics showed that training to voluntarily move in response to a premonitory urge can reduce tic symptoms. Other behavioral therapies, such as biofeedback or supportive therapy, have not been shown to reduce tic symptoms. However, supportive therapy can help a person with TS better cope with the disorder and deal with the secondary social and emotional problems that sometimes occur.

Is TS inherited?

Evidence from twin and family studies suggests that TS is an inherited disorder. Although early family studies suggested an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance (an autosomal dominant disorder is one in which only one copy of the defective gene, inherited from one parent, is necessary to produce the disorder), more recent studies suggest that the pattern of inheritance is much more complex. Although there may be a few genes with substantial effects, it is also possible that many genes with smaller effects and environmental factors may play a role in the development of TS.

Genetic studies also suggest that some forms of ADHD and OCD are genetically related to TS, but there is less evidence for a genetic relationship between TS and other neurobehavioral problems that commonly co-occur with TS. It is important for families to understand that genetic predisposition may not necessarily result in full-blown TS; instead, it may express itself as a milder tic disorder or as obsessive-compulsive behaviors. It is also possible that the gene-carrying offspring will not develop any TS symptoms.

The gender of the person also plays an important role in TS gene expression. At-risk males are more likely to have tics and at-risk females are more likely to have obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Genetic counseling of individuals with TS should include a full review of all potentially hereditary conditions in the family.

What is the prognosis?

Although there is no cure for TS, the condition in many individuals improves in the late teens and early 20s. As a result, some may actually become symptom-free or no longer need medication for tic suppression. Although the disorder is generally lifelong and chronic, it is not a degenerative condition. Individuals with TS have a normal life expectancy. TS does not impair intelligence. Although tic symptoms tend to decrease with age, it is possible that neurobehavioral disorders such as ADHD, OCD, depression, generalized anxiety, panic attacks, and mood swings can persist and cause impairment in adult life.

What is the best educational setting for children with TS?

Although students with TS often function well in the regular classroom, ADHD, learning disabilities, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and frequent tics can greatly interfere with academic performance or social adjustment. After a comprehensive assessment, students should be placed in an educational setting that meets their individual needs. Students may require tutoring, smaller or special classes, and in some cases special schools.

All students with TS need a tolerant and compassionate setting that both encourages them to work to their full potential and is flexible enough to accommodate their special needs. This setting may include a private study area, exams outside the regular classroom, or even oral exams when the child’s symptoms interfere with his or her ability to write. Untimed testing reduces stress for students with TS.

The above information and more can be found by clicking here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 26th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering a movie screening of FIXED.

FIXED Mon., Oct. 26 from 1-3 p.m. (movie is 60 minutes, with a discussion afterwards for those who can stay) in room 1504.

What is FIXED about??

A haunting, subtle, urgent documentary, FIXED questions commonly held beliefs about disability and normalcy by exploring technologies that promise to change our bodies and mind forever. Told primarily through the perspectives of five people with disabilities: a scientist, journalist, disability justice educator, bionics engineer and exoskeleton test pilot, FIXED takes a close look at the implications of emerging human enhancement technologies for the future of humanity.

Check out the trailer here.

Please contact the Office of Special Services if you have questions or would like to schedule a discussion of the topic or a showing of the movie in your class.

Kathy Cook, Associate Dean

Office of Special Services

Ext. 4544

Posted in Announcements, Events, Free Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 25th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

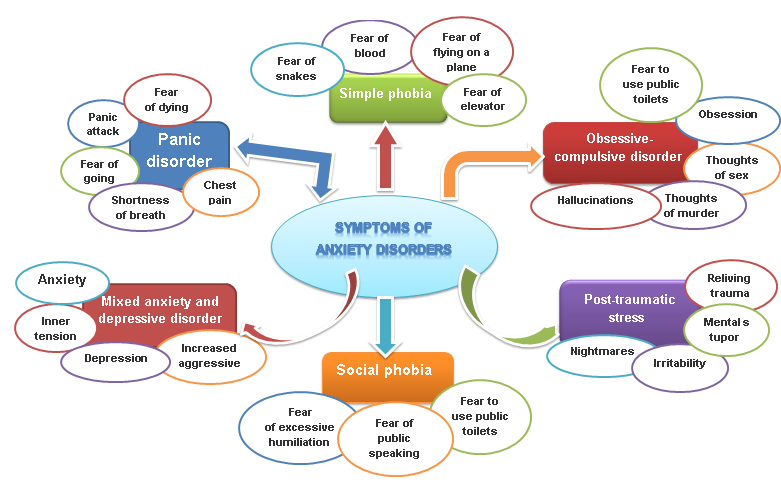

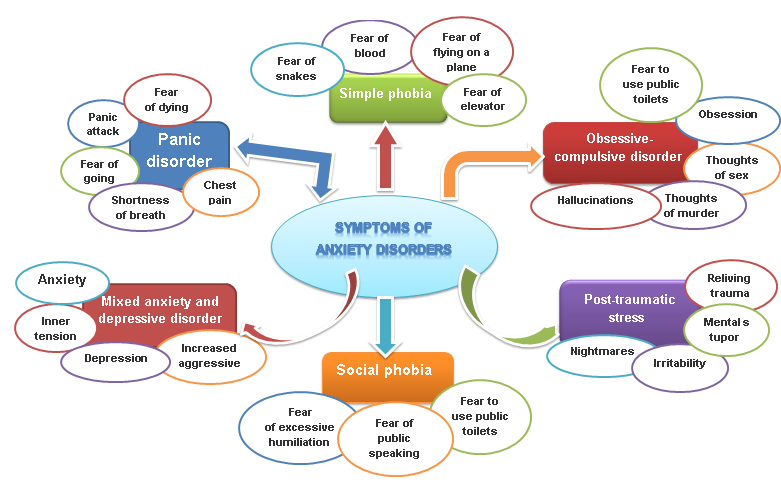

What Are the Types of Anxiety Disorders?

There are several recognized types of anxiety disorders, including:

- Panic disorder: People with this condition have feelings of terror that strike suddenly and repeatedly with no warning. Other symptoms of a panic attack include sweating, chest pain, palpitations (unusually strong or irregular heartbeats), and a feeling of choking, which may make the person feel like he or she is having a heart attack or “going crazy.”

- Social anxiety disorder: Also called social phobia, social anxiety disorder involves overwhelming worry and self-consciousness about everyday social situations. The worry often centers on a fear of being judged by others, or behaving in a way that might cause embarrassment or lead to ridicule.

- Specific phobias: A specific phobia is an intense fear of a specific object or situation, such as snakes, heights, or flying. The level of fear is usually inappropriate to the situation and may cause the person to avoid common, everyday situations.

- Generalized anxiety disorder: This disorder involves excessive, unrealistic worry and tension, even if there is little or nothing to provoke the anxiety.

What Are the Symptoms of an Anxiety Disorder?

Symptoms vary depending on the type of anxiety disorder, but general symptoms include:

- Feelings of panic, fear, and uneasiness

- Problems sleeping

- Cold or sweaty hands and/or feet

- Shortness of breath

- Heart palpitations

- An inability to be still and calm

- Dry mouth

- Numbness or tingling in the hands or feet

- Nausea

- Muscle tension

- Dizziness

What Causes Anxiety Disorders?

The exact cause of anxiety disorders is unknown; but anxiety disorders — like other forms of mental illness — are not the result of personal weakness, a character flaw, or poor upbringing. As scientists continue their research on mental illness, it is becoming clear that many of these disorders are caused by a combination of factors, including changes in the brain and environmental stress.

Like other brain illnesses, anxiety disorders may be caused by problems in the functioning of brain circuits that regulate fear and other emotions. Studies have shown that severe or long-lasting stress can change the way nerve cells within these circuits transmit information from one region of the brain to another. Other studies have shown that people with certain anxiety disorders have changes in certain brain structures that control memories linked with strong emotions. In addition, studies have shown that anxiety disorders run in families, which means that they can at least partly be inherited from one or both parents, like the risk for heart disease or cancer. Moreover, certain environmental factors — such as a trauma or significant event — may trigger an anxiety disorder in people who have an inherited susceptibility to developing the disorder.

Anxiety disorders affect millions of adult Americans. Most anxiety disorders begin in childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. They occur slightly more often in women than in men, and occur with equal frequency in whites, African-Americans, and Hispanics.

How Are Anxiety Disorders Diagnosed?

If symptoms of an anxiety disorder are present, the doctor will begin an evaluation by asking you questions about your medical history and performing a physical exam. Although there are no lab tests to specifically diagnose anxiety disorders, the doctor may use various tests to look for physical illness as the cause of the symptoms.

If no physical illness is found, you may be referred to a psychiatrist, psychologist, or another mental health professional who is specially trained to diagnose and treat mental illnesses. Psychiatrists and psychologists use specially designed interview and assessment tools to evaluate a person for an anxiety disorder.

The doctor bases his or her diagnosis on the patient’s report of the intensity and duration of symptoms — including any problems with daily functioning caused by the symptoms — and the doctor’s observation of the patient’s attitude and behavior. The doctor then determines if the patient’s symptoms and degree of dysfunction indicate a specific anxiety disorder.

How Are Anxiety Disorders Treated?

Fortunately, much progress has been made in the last two decades in the treatment of people with mental illnesses, including anxiety disorders. Although the exact treatment approach depends on the type of disorder, one or a combination of the following therapies may be used for most anxiety disorders:

- Medication: Drugs used to reduce the symptoms of anxiety disorders include anti-depressants and anxiety-reducing drugs.

- Psychotherapy: Psychotherapy (a type of counseling) addresses the emotional response to mental illness. It is a process in which trained mental health professionals help people by talking through strategies for understanding and dealing with their disorder.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy: This is a particular type of psychotherapy in which the person learns to recognize and change thought patterns and behaviors that lead to troublesome feelings.

- Dietary and lifestyle changes.

- Relaxation therapy.

Can Anxiety Disorders Be Prevented?

Anxiety disorders cannot be prevented; however, there are some things you can do to control or lessen symptoms:

- Stop or reduce consumption of products that contain caffeine, such as coffee, tea, cola, energy drinks, and chocolate.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist before taking any over-the-counter medicines or herbal remedies. Many contain chemicals that can increase anxiety symptoms.

- Seek counseling and support if you start to regularly feel anxious with no apparent cause.

The above information and more can be found here, here and here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 22nd, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

Facts about Dysthymia

Dysthymia (dis-THIE-me-uh) is a mild but long-term (chronic) form of depression. Symptoms usually last for at least two years, and often for much longer than that. Dysthymia interferes with your ability to function and enjoy life.

With dysthymia, you may lose interest in normal daily activities, feel hopeless, lack productivity, and have low self-esteem and an overall feeling of inadequacy. People with dysthymia are often thought of as being overly critical, constantly complaining and incapable of having fun.

Dysthymia symptoms in adults may include:

- Loss of interest in daily activities

- Sadness or feeling down

- Hopelessness

- Tiredness and lack of energy

- Low self-esteem, self-criticism or feeling incapable

- Trouble concentrating and trouble making decisions

- Irritability or excessive anger

- Decreased activity, effectiveness and productivity

- Avoidance of social activities

- Feelings of guilt and worries over the past

- Poor appetite or overeating

- Sleep problems

In children, dysthymia sometimes occurs along with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), behavioral or learning disorders, anxiety disorders, or developmental disabilities. Examples of dysthymia symptoms in children include:

- Irritability

- Behavior problems

- Poor school performance

- Pessimistic attitude

- Poor social skills

- Low self-esteem

Dysthymia symptoms usually come and go over a period of years, and their intensity can change over time. But typically symptoms don’t disappear for more than two months at a time. In general, you may find it hard to be upbeat even on happy occasions — you may be described as having a gloomy personality.

When dysthymia starts before age 21, it’s called early-onset dysthymia. When it starts after that, it’s called late-onset dysthymia.

When to see a doctor

It’s perfectly normal to feel sad or upset sometimes or to be unhappy with stressful situations in your life. But with dysthymia, these feelings last for years and interfere with your relationships, work and daily activities.

Because these feelings have gone on for such a long time, you may think they’ll always be part of your life. But if you have any symptoms of dysthymia, seek medical help. If not effectively treated, dysthymia commonly progresses into major depression. Sometimes, a major depression episode occurs in addition to dysthymia — this is called double depression.

Talk to your primary care doctor about your symptoms. Or seek help directly from a mental health provider. If you’re reluctant to see a mental health professional, reach out to someone else who may be able to help guide you to treatment, whether it’s a friend or loved one, a teacher, a faith leader, or someone else you trust.

The above information and more can be found here and here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 22nd, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering a movie screening of FIXED.

FIXED Mon., Oct. 26 from 1-3 p.m. (movie is 60 minutes, with a discussion afterwards for those who can stay) in room 1504.

What is FIXED about??

A haunting, subtle, urgent documentary, FIXED questions commonly held beliefs about disability and normalcy by exploring technologies that promise to change our bodies and mind forever. Told primarily through the perspectives of five people with disabilities: a scientist, journalist, disability justice educator, bionics engineer and exoskeleton test pilot, FIXED takes a close look at the implications of emerging human enhancement technologies for the future of humanity.

Check out the trailer here.

Please contact the Office of Special Services if you have questions.

Kathy Cook, Associate Dean

Office of Special Services

Ext. 4544

Posted in Announcements, Events, Free Tagged with: disability awareness month, FIXED, OSS

October 21st, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

International Stuttering Awareness Day – October 22

Did You Know?

- Stuttering is a communication disorder involving disruptions, or dysfluencies, in a person’s speech, but there are nearly as many ways to stutter as there are people who stutter.

- The National Stuttering Association is a non-profit organization – the largest in the world – started in 1977, dedicated to bringing hope and empowerment to children and adults who stutter, their families, and professionals through support, education, advocacy, and research. Our organization is largely volunteer run and member-donation funded.

Common Myths about Stuttering

People have found stuttering confusing for centuries, and as with so many mysteries, they have tried to explain it with folklore. For instance, people in some cultures once believed that a child stuttered because his mother saw a snake during pregnancy or because he ate a grasshopper as a toddler. We now know that stuttering is probably neurological in origin, may have genetic origins, and often results in emotional components.

However, myths about stuttering persist today. Here are just a few of them:

- People stutter because they are nervous. Because fluent speakers occasionally become more disfluent when they are nervous or under stress, some people assume that people who stutter do so for the same reason. While people who stutter may be nervous because they stutter, nervousness is not the cause.

- People who stutter are shy and self-conscious. Children and adults who stutter often are hesitant to speak up, but they are not otherwise shy by nature. Once they come to terms with stuttering, people who stutter can be assertive and outspoken. Many have succeeded in leadership positions that require talking.

- Stuttering is a psychological disorder. Emotional factors often accompany stuttering but it is not primarily a psychological condition. Stuttering treatment often includes counseling to help people who stutter deal with attitudes and fears that may be the result of stuttering.

- People who stutter are less intelligent or capable. People who stutter are disproving this every day. The stuttering community has its share of scientists, writers, and college professors. People who stutter have achieved success in every profession imaginable.

- Stuttering is caused by emotional trauma. Some have suggested that a traumatic episode may trigger stuttering in a child who already is predisposed to it, but the general scientific consensus is that this is not usually the root cause of the disorder.

- Stuttering is caused by bad parenting. When a child stutters, it is not the parents’ fault. Stress in a child’s environment child can exacerbate stuttering, but is not the cause.

- Stuttering is just a habit that people can break if they want to. Although the manner in which people stutter may develop in certain patterns, the cause of stuttering itself is not due to a habit. Because stuttering is a neurological condition, many, if not most, people who stutter as older children or adults will continue to do so—in some fashion—even when they work very hard at changing their speech.

- Children who stutter are imitating a stuttering parent or relative. Stuttering is not contagious. Since stuttering often runs in families, however, children who have a parent or close relative who stutters may be at risk for stuttering themselves. This is due to shared genes, not imitation.

- Forcing a left-handed child to become right-handed causes stuttering. This was widely believed early in the 20th century but has been disproven in most studies since 1940. Although attempts to change handedness do not cause stuttering, the stress that resulted when a child was forced to switch hands may have exacerbated stuttering for some individuals.

- Identifying or labeling a child as a stutterer results in chronic stuttering. This was the premise of a famous study in 1939. The study was discredited decades ago, but this outdated theory still crops up occasionally. Today, we know that talking about stuttering does not cause a child to stutter.

These are just a few of the common myths out there. Instead of perpetuating such myths, it is important to have the Facts About Stuttering!

The above information and more can be found here and here.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month, OSS

October 19th, 2015 by pio@shoreline.edu

In honor of Disability Employment Awareness Month, the Office of Special Services (OSS) is working to raise awareness of disabilities by offering daily facts and tips about people with disabilities and living with disability. Please take a minute to read and broaden your understanding.

Facts About Eczema

What is eczema?

Eczema (atopic dermatitis) is a recurring, non-infectious, inflammatory skin condition affecting one in three Australasians at some stage throughout their lives. The condition is most common in people with a family history of an atopic disorder, including asthma or hay fever.

Atopic eczema is the most common form of the disease among Australasians. The skin becomes red, dry, itchy and scaly, and in severe cases, may weep, bleed and crust over, causing the sufferer much discomfort. Sometimes the skin may become infected. The condition can also flare and subside for no apparent reason.

Although eczema affects all ages, it usually appears in early childhood (in babies between two-to-six months of age) and disappears around six years of age. In fact, more than half of all eczema sufferers show signs within their first 12 months of life and 20 per cent of people develop eczema before the age of five.

Most children grow out of the condition, but a small percentage may experience severe eczema into adulthood. The condition can not only affect the individual sufferer, but also their family and friends. Adult onset eczema is often very difficult to treat and may be caused by other factors such as medications.

What causes eczema?

The exact cause of eczema is unknown – it appears to be linked to the following internal and external triggers:

Internal

- A family history of eczema, asthma or hay fever (the strongest predictor): if both parents have eczema, there is an 80 percent chance that their children may also develop eczema

- Some foods and alcohol: dairy and wheat products, citrus fruits, eggs, nuts, seafood, chemical food additives, preservatives and colorings

- Stress

External

- Irritants: tobacco smoke, chemicals, weather (hot and humid or cold and dry conditions) and air conditioning or overheating

- Allergens : house dust mites, molds, grasses, plant pollens, foods, pets and clothing, soaps, shampoos and washing

What are the symptoms of eczema?

- Moderate-to-severely itching skin

- rash – dry, red, patchy or cracked skin. Commonly it appears on the face, hands, neck, inner elbows, backs of the knees and ankles, but can appear on any part of the body.

- Skin weeping watery fluid

- Rough, “leathery,” thick skin

How does eczema affect people?

Although eczema in itself is not a life-threatening disease, it can certainly have a debilitating effect on a sufferer, their careers and their family’s quality of life. Night-time itching can cause sleepless nights and place a significant strain upon relationships. Eczema ‘flare-ups’ can often lead to absenteeism from work, school, personal activities & responsibilities. For some severe sufferers it can also mean hospitalizations & costly treatments.

Is there a cure for eczema?

Although there is no known cure for eczema and it can be a lifelong condition, treatment can offer symptom control.

How do you diagnose eczema?

Only a doctor or skin specialist, usually a Dermatologist, can formally diagnose eczema. An accurate diagnosis requires a complete skin examination, a thorough medical history and the presence of a chronically recurring rash with intense itching that is consistent with eczema. Itching is an important clue to diagnosing eczema. If an itch is not present, chances are that the problem is not eczema.

While there is no test to determine whether a person has eczema, tests may be conducted to rule out other possibilities. The above information and more can be found at www.exzema.org.au.

Posted in Announcements Tagged with: disability awareness month